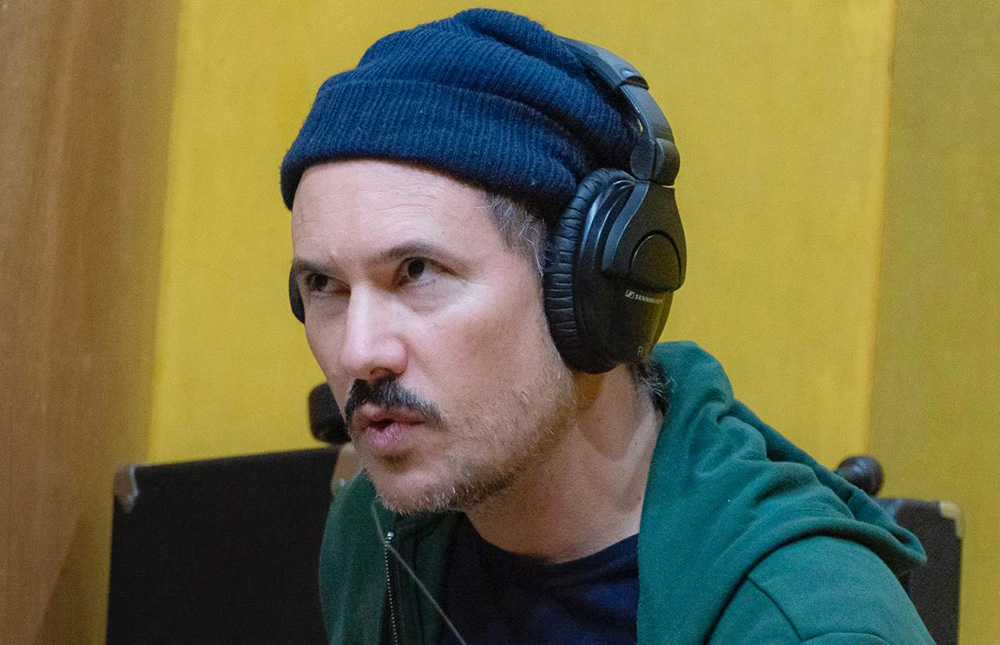

From Egypt to Somalia, Sudan to Lebanon, North Africa to the Arabian Peninsula, Jannis Stürtz does much more than music tourism on his frequent trips around the region. More than a traveler, he’s a cultural explorer, an archaeologist disguised as a DJ. His mission is much more commendable: he digs and unearths old records from the Arab world from the 1960s to the 1980s to reissue them on his label, Habibi Funk Records.

Based in Berlin, Germany, Habibi Funk didn’t get its name by chance. The term doesn’t define a genre of music, although it may seem so, but rather a variety of Arabic music that this label has fallen in love with. Not surprisingly, “habibi” in Arabic means “my love” or “my beloved”, reflecting the label’s passion for these eclectic sounds. There’s an undeniable emotional connection to the artists from different eras and regions that Habibi Funk Records has collected and reissued. Jannis Stürtz, the label’s cofounder, also works as a DJ under the same name, promoting the sounds he recues and giving a duality to Habibi Funk as a brand.

“Habibi Funk is dedicated to re-releasing a style of music that historically never existed as a musical genre. We use the term to describe a certain sound that we like from the countries of the Arab world,” begins the press release for one of the label’s first and most celebrated compilations, An Eclectic Selection of Music from the Arab World. The text also notes that the songs chosen come from distant places and were created under different circumstances. “Some were written and recorded during war times, others in exile,” it adds. However, despite the differences, there’s an underlying musical connection. And that’s essentially the label’s interest: musical endeavors in which artists from the Arab world combine local and regional influences with musical interests from outside the region.

“Eclectic sounds from the Arab world,” sums up the label in its brief profile. It’s worth emphasizing the “eclectic” nature of Habibi Funk’s catalogue: it covers a wide range of artists from different regions and eras. Even though the label’s name suggests that it’s all about funk music, its focus goes beyond that. More than a genre or a style, Habibi Funk could be defined as a music scene rediscovered and introduced decades later by the label. A timeless and transversal movement of global groove, based on a powerful crossover: soul, funk, reggae, jazz and disco, among other Western music, mixed with Arabic music from the Middle East and North Africa.

Every story has a beginning, and Habibi Funk’s story dates back to a trip Jannis Stürtz made to Morocco in 2012 as tour manager for Blitz The Ambassador, who was performing at a festival in the capital, Rabat. He then took the opportunity to stay a few more days and visit Casablanca, a legendary city that was the nerve center of the Moroccan music scene and record industry in the 1960s and 1970s. There, wandering the rundown streets of the medina and browsing through secondhand shops, he discovered his first lost treasure: a 7” vinyl record by a forgotten Moroccan band named Fadoul et Les Privileges. The single was “Sid Redad”, a cover of James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” sung in Arabic and backed by a rawly recorded three-piece band.

“The first time I heard the record, I was blown away,” Jannis confessed in a letter written in 2015, shortly before releasing his label’s first compilation, Al Zman Saib — and Fadoul’s first LP 45 years after his music was originally released. “It’s hard to describe the music without having listened to it, but I somehow ended up summarizing it as Arabic funk played with a punk attitude.” He became obsessed with the record, but nobody seemed to know anything about the artist, who had passed away in 1991. Not even Google helped. “A true gem forgotten about through the passages of time,” he wrote. More trips to Morocco followed, countless taxis, many phone calls, and street conversations. A search of almost three years, gathering information from other Moroccan artists, until he found the family of Fadoul. One of his sisters shared beautiful stories from her brother’s life: “A creative spirit who painted, played theatre, and eventually ended up dedicating most of his energy to music. He spent some time living in Paris, soaking up the music of James Brown, Free and other American bands, laying the foundation of his unique mix of Arabic and Western musical influences.”

Habibi Funk not only reissues original vintage albums and singles but also expertly takes on the task of creating excellent compilations. There are various artists’ compilations, such as the series An Eclectic Selection of Music from the Arab World (the first volume in 2017 and the second volume in 2021), and some charity albums (Solidarity with Beirut in 2020 and Solidarity with Libya in 2023). However, they also create compilations for specific artists, such as the Fadoul singles included in the label’s inaugural release. Since then, they have released significant compilations showcasing the work of artists such as Al Massrieen (2017’s Modern Music), Sharhabil Ahmed (2020’s The King of Sudanese Jazz), Majid Soula (2021’s Chant Amazigh), Hamid El Shaeri (2022’s The SLAM! Years: 1983 – 1988), and Ibrahim Hesnawi (2023’s The Father of Libyan Reggae).

Habibi Funk specializes in discovering and restoring wonderful lost records. But the label also deals with forgotten recordings by well-known stars, such as Hamid Al Shaeri, a Libyan-born singer-songwriter living in Egypt, considered one of the greatest figures of Arabic pop. This is the focus of The SLAM! Years, a compilation that features Hamid’s first recordings, between 1983 and 1988, for the Egyptian label SLAM!, before he became a figurehead of the Al Jeel (the Egyptian version of popular foreign music, such as pop and rock). At the time, in the early 1980s, Hamid had just left Libya to continue his career in Egypt, via London, where he recorded his first album. His distinctive sound was essentially based on synthesizers, so it was very important to acquire them in time. “Whenever a new one [synthesizer] would come out, we would have to buy it immediately, otherwise someone else would get their hands on that sound,” reads the only statement in the press release.

Jannis Stürtz continues to passionately explore record stores in Cairo, Beirut, Amman, Dubai, Manama, Marrakech, and Tunis, among other places. These spaces, filled with shelves still stocked with cassettes and vinyl, have played a fundamental role in shaping musical culture — they are the foundation for sustaining the stories of the past in the present. But embarking on these missions to distant places is no easy task. These musical treasures are discovered with great enthusiasm, but they aren’t always immediately available for reissue by Habibi Funk Records. Sometimes, everything flows smoothly. But other times, these projects are blocked by technological difficulties or even ethical reasons. “If you’re a European or Western label and you’re dealing with non-European artists’ music, there’s obviously a special responsibility to make sure you don’t reproduce historic economic patterns of exploitation, which is the number one thing when it comes to the post-colonial aspect of what we are doing,” Jannis told The Vinyl Factory in 2017, already claiming his awareness of the political aspects of the label’s work.

In a 2018 interview with Mille, the first media dedicated to Arab youth culture, Jannis delved a little more into Habibi Funk’s ethical stance and how to navigate the debate over cultural appropriation: “If you run a label that rereleases music from outside of the European world, it automatically puts you in a position of responsibility not to repeat historical patterns of economic exchange, of communication, of culture.” He added that the label split the profits with the artists or their families 50/50. “We don’t own copyrights.”

A distinctive visual signature of Habibi Funk Records is its cover art. On the one hand, it avoids stereotypical imagery: “We’re not going to have camels on our covers. And I mean, you have those covers in the region, but it’s something different if I do it,” said Jannis. On the other hand, it’s written in Arabic: “We’re trying to make sure our covers are made in Arabic. We try to use Arabic in our social media communication — at least with the big stuff — and it’s not because I don’t think that the demographic that follows us in the Arab world doesn’t speak English. I think they do. It’s more of a symbolic thing since we’re dealing with music that has Arabic lyrics — so I feel like that should be reflected in the way you hear about it.”