If you were anywhere near the jazz scene in America in the 1960s, chances are, you were into Bossa Nova. But how did American jazz greats like Stan Getz become equally as synonymous with the genre as its own Brazilian founders? You can chalk it up to music being a connecting fiber and a universal language that we all speak. Here’s our sparknotes edition.

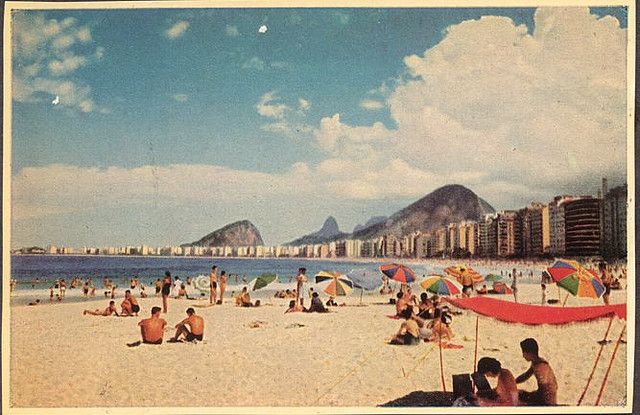

Picture this: It’s the late 1950s and the Brazilian beaches are teaming with young musicians high on life and eager to jam. Rio, always a cultural hub, was a city that welcomed artists with open arms and the sand was where they went to let loose all hours of the day. A crew of middle-class students and players, legends like Antônio Carlos Jobim and João Gilberto among them, landed on a fresh new sound. A soft samba that fused traditional rhythms with jazz riffs, and whose essence was entirely romantic: Bossa Nova. Literally translated to “New Trend” or “New Wave”.

As these respective masters of production and guitar honed in on the sound, more Bossa leaders joined the ranks. Well-known names like Vinícius de Moraes, Sérgio Mendes, and Nara Leão, took the genre and ran with it, hosting parties and laying down records in a huge sonic boom. As the 1960s rolled around, highly revered American disc jokeys like Felix Grant were introduced to the precious vinyl by way of music trades and fellow international jokeys. The more that the genre graced American airwaves, the more interest our country garnered in the sounds and rhythms of other cultures.

As it usually tends to do, the U.S. government saw this as an opportunity to use great American musicians like Charlie Byrd, Herbie Mann, Stan Getz, and Dave Brubeck (among dozens of others) as a cross-country olive branch to quell political tensions between the U.S. and much of the southern continent. These South American tours brought some of the world’s most talented jazz musicians face to face with Brazil’s Bossa Nova pioneers resulting, inevitably, in jams laid down to wax and engraved into history forever.

Whether they were recorded overseas or right on American soil, these legends understood what was at the soul of sounds from either side of the spectrum. They were proud to generously share, collaborate, trade, and collectively nerd out on brilliant new avenues together. In short, you can view Bossa Nova as a merging of the very best of two countries’ most exceptional artists. A sound that encapsulates Brazilian tendencies to let loose, stitched together by the mathematical chiseling only jazz can sculpt.