Resident Mexican DJ and all-around musical badass, Pablo Borchi, gives us his perspective on the rise of afrobeats on dance floors around the world, and how the genre’s brightest stars are adapting to its increased expansion of new audiences.

If you are into different styles of global music then you’ve probably realized that in the past years afrobeats have been growing in popularity across the globe.

For me, the idea that afrobeats were the sound of the future started to get into my head when I listened to Mina’s 2017 Boiler Room set. That set was just perfect. It had the right mix of underground music clashing against classic and new hits, many mashups and remixes included, all in a very fun and surprising manner. It had the same fresh energy I felt when global bass started to become big a couple of years earlier. And actually, it wasn’t quite an afrobeats set, it had a good bunch of Jamaican dancehall artists, but it all anchored around artists such as J Hus and Gafacci, which was enough to make me turn my eyes to what was coming out from Nigeria and Ghana via the UK.

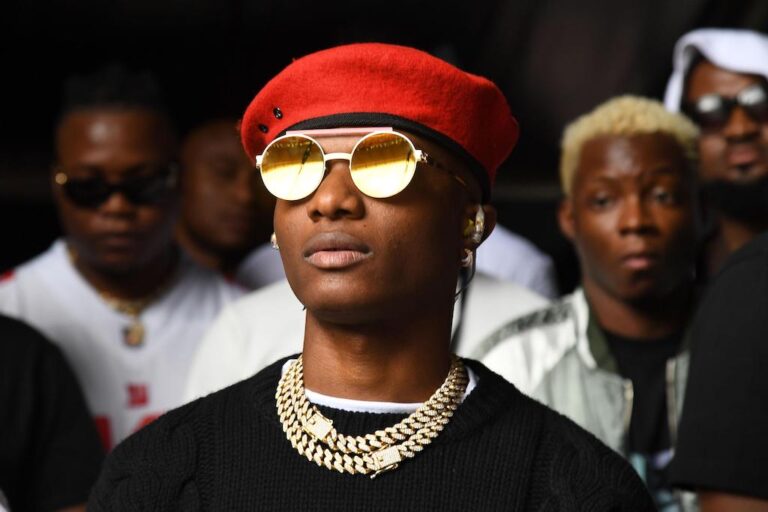

Fast forward to 2020 and afrobeats are no longer something that some niche DJs are championing to all kinds of globalist audiences. This style which draws influences from post-Fela Kuti melodies and rhythms, dancehall, hip hop, feel good lyrics and super sweet pop sensibility has expanded way beyond its countries of origin and their migrant communities in Europe and the U.S. This short list of artists will give you a clear idea of the kind of sound I’m referring to: Wiz Kid, Mr Eazi, Tina Sawage, Davido.

Wiz Kid – “Joro”

Mr Eazi – “Pour Water”

Tiwa Savage – “Koroba”

Davido – “Fall”

Ever since Wiz Kid collaborated with Drake on the song “One Dance” back in 2016, afrobeats’ artists have been crossing over to all kinds of mainstream spots to the point were in the UK in 2019, Afrobeats artists collectively spent 86 weeks in the Official Chart Top 40. While in the U.S., also in 2019, Beyoncé released a new album as a soundtrack for The Lion King heavily focused on the afrobeats sound, featuring some of the usual suspects of that scene like Burna Boy, Tekno, Mr. Eazi, Tiwa Savage and more.

Beyoncé – “Jara A E” ft. Burna Boy

After proving their success in English speaking markets, afrobeats artists are starting to interact more and more with the Latin market. In the past years we’ve seen all kinds of crossovers in tracks such as “Como Un Bebe” by J. Balvin & Bad Bunny ft. Mr. Eazi and Maluma doing a new set of Spanish lyrics on Aya Nakamura’s “Djadja”.

J Balvin & Bad Bunny ft. Mr. Eazi

Aya Nakamura ft. Maluma – Djadja

This crossover could suggest that it’s only a matter of time before their sound invades all of Latin America with the same hype it’s been doing in the biggest English speaking markets. However, I think this process will be a little bit slower than expected.

From my experience from DJing in many Mexican dance floors I can tell you that you can surely squeeze a couple of afrobeats tracks in your average reggaeton set (both mainstream and alternative) but people don’t seem to react too strongly to them, even when you play the J. Balvin type of collabs.

There can be many factors behind this, but I believe this has a lot to do with how people relate to African culture, which works a bit differently between the UK/U.S. and Latin America.

Apparently a lot of the rise in popularity of afrobeats is closely related with the growth of the pride behind being African within the African diaspora. This is something that stars like Tina Sawage and Davido have expressed in recent interviews.

“When I lived in America, being African wasn’t cool. The first thing you’d hear about Africa is scams and poverty. Now, people talk about the culture, the food. Now everybody wants to make African music.” – Davido

It is possible that the spread of better internet access throughout Africa has helped to communicate its culture more effectively to the UK’s and U.S.’ audiences. I’m guessing also that the increase in study abroad students and overall migration coming from Nigeria and Ghana in the past years has played a part in transmitting this music to the middle class and privileged non-African audiences. And, there must be some sort of “behind the curtains” investment from Anglo institutions on African culture for exports going on to counteract Muslim and Chinese cultural and economic influences in the region.

Whatever may be the case, the fact is that in the past years there have been more and more projects re-valuing the pride of being African in both the UK and America, and that is why it is more common to see movies like Black Panther and listen to news such as the rapper Ludacris obtaining his Gabon nationality.

For Latin America this works a bit differently. Firstly, recent African migration to Latin America is much smaller than those happening to Europe and the U.S.

Secondly, in many Latin American countries the afro descendant identity is still in its first steps towards being understood by governments as something beyond just a tiny element of the bigger “Latin” identity. For example, in Mexico, just this year, the national census is including a category where people can identify themselves as Afro descendants.

As the singer from Choc Quib Town (“Goyo”) mentions during the launch of his Conciencia Collective, arguments that disguise blackness into a bigger Latin identity are sometimes used to minimize discriminatory practices against Afro descendants – (i.e. the phrase: “No hay racismo en América Latina. Estamos todos mezclados”).

This way of understanding Afro descendence is an element that can help to frame the connection of Latin America with Africa as something “ancient”, exotic, almost folkloric, and not quite modern.

That could be why people can get a little bit confused when they hear a new afrobeats tune in the middle of a mainstream reggaeton set. Many times they don’t recognize the high life inspired synth licks and snare patterns as something super new and trendy. Instead, these elements come across to the audience as something related to traditional “world music”, not quite suitable for the night club’s VIP area.

Because of this, I believe that for afrobeats to become really big in Latin America they need to adapt the way they communicate their sound to local audiences. The best way to do it is to do it is via a new Afro-Latinx tag that can put them side by side with other non – afro descendant artists without making them lose their signature vibe.

Luckily for this scene, this is a process that has already started and we can find a couple of examples of artists working on developing this Afro-Latinx identity and sound both in the underground scenes as well as the mainstream. Here is a list of tracks and artists that give a broad picture of where the new Afro-Latinx sound is going, and how they contribute differently to this new Afro-Latinx sound.

First stop is where Spanish and other white artists that create their own version of what afrobeats sounds to them.

These can include tracks like C.Tangana’s spanish version of J Hus’ “Did You See”, Indee’s “Gloria” or Frikstailers “Afrotrip”. Whether the artist works on the mainstream circuit, alternative scenes or the electronic underground, once a non-Black artist does an afrobeats track then Latin audiences can experience this sound without relating it directly to Africa. This is not a very “Afro-Latinx” thing to do, but it’s a start to get into their heads. Once in their heads, it will be (hopefully) easier to explain where this type of music came from.

J Hus – “Did You See (C. Tangana Remix)”

Indee – “Gloria”

Frikstailers – “Afrotrip”

The next bunch of songs come from mainstream artists with Latin heritage that team up with Afro descendent artists coming from Latin America. The examples here are ChocQuibTown & Becky G – “Que Me Baile” and Cardi B & Anitta – “Me Gusta”.

ChocQuibTown & Becky G – “Que Me Baile”

Cardi B & Anitta – “Me Gusta”

There are also a couple of mainstream artists that embrace an Afrolatinx sound and identity without necessarily teaming up with a black artist. Here I would like to mention Myke Towers, who could easily be playing the “white artist” card but instead is exploring his Afro roots through his music.

And I would also like to throw the Black Eyed Peas into the list. Their latest album Translations is heavily focused on reggaeton. However, in “Vida Loca ” they go full-on afrobeats while still having Nicky Jam featured on the track. I think this is a hint at how both genres could mix to develop a new Afro-Latinx sound, and I am expecting that in their next album the BEP will probably do it by having a track where they put Davido singing alongside ChocQuibTown.

Moving beyond the mainstream, the examples that I like the most are when there is a new Latin version of afrobeats developed as a result of direct migration between both continents.

The clearer example is the Bakoso sound coming from Santiago de Cuba and championed by Dj Jigüe. The Cuban political system is known for allowing exchanges between local and African doctors. This results in afrobeats being passed over to Cuban nationals and later becoming a new mix of both sound identities. Once the Bakoso documentary is released to a broader public it will be easier to trace down the tracklist of artists for this scene. But meanwhile I recommend you check out this awesome track by Ozkaro Dlga2 & Dj Minium

Another example of this phenomena is the Brime sound coming up from Brazil, which is defined as a combination of UK’s grime and Brazilian funk. I’m not sure how precise this argument/musical connection is, but apparently this sound is caused by the increased migration of Nigerians to Brazil, who are also very connected to the other Nigerian diaspora living in the UK.

You can check out Brazil’s Cesrv’s Brime EP to get to know this sound, which is an interesting take on the way African via UK influences collide with Brazilian music. I think if artists like Cesrv start putting the focus on crossovers between grime and afrobeats for their experiments with baile funk, then we will probably have a very interesting Afro-Latinx sound coming out from that scene very soon.

To close out the list I want to mention Ghetto Kumbe, which is a nice example of new electronic music made by Latin Afro descendants mixing both heritages. In tracks like “Sola” or “Dagbani Dance” they fuse cumbia and azonto elements in a very refreshing way, which only needs a bit more pop sensibility to have that signature afrobeats vibe. I can imagine them remixing mainstream artists like Wizkid or Tina Sawage as a great way to introduce Latin audiences to them.

As you can see, none of these examples include artists coming directly from Africa. But don’t worry, this is only an intermediate step. I think that once the Afro-Latinx concept is solidified in the region then we will start to see all kinds of African artists collaborating with Latin ones and spreading the afrobeats vibe through the entire continent.